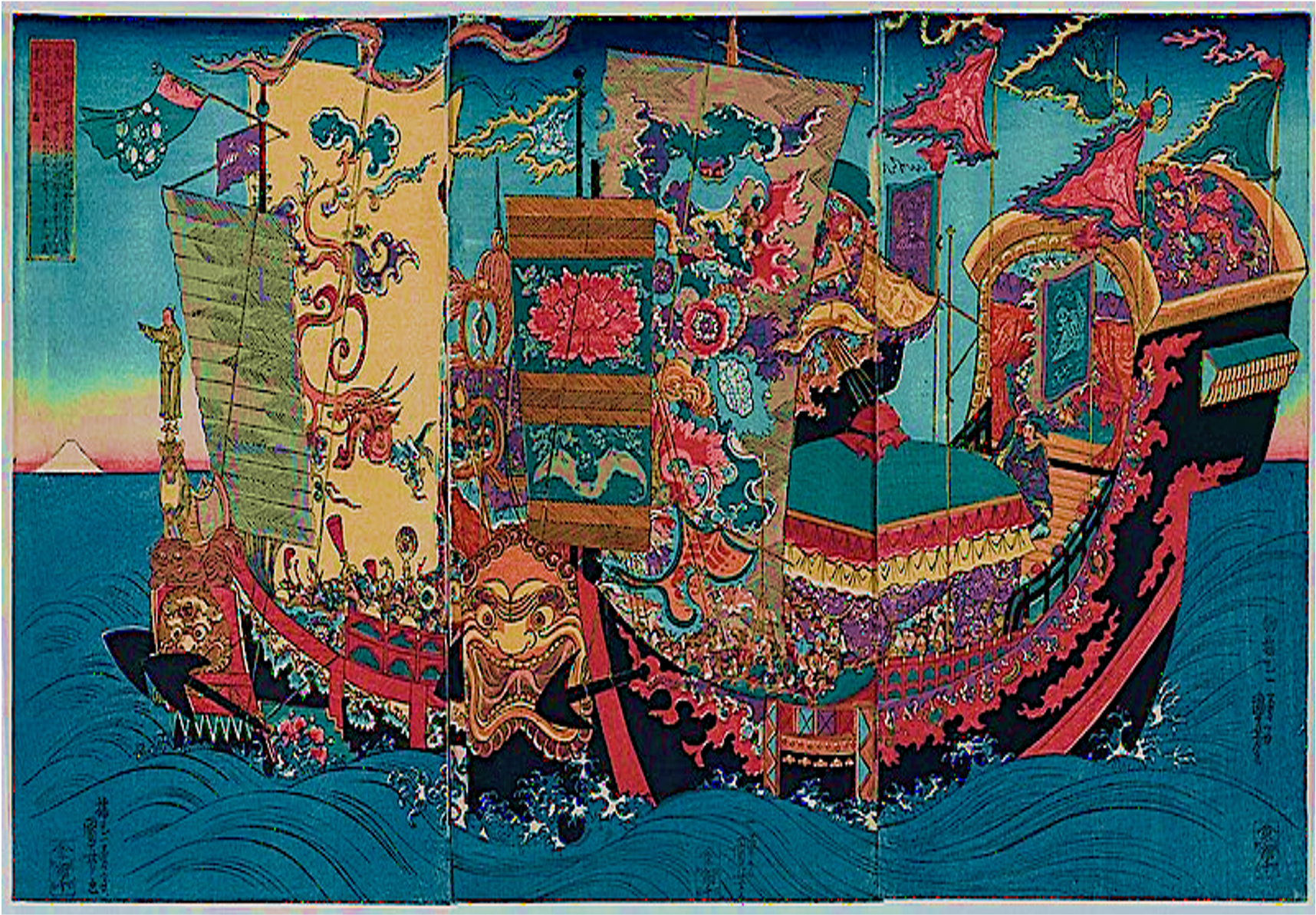

Early in the Ming Dynasty (1405-1433 CE) the Yǒng Lè (永樂) Emperor dispatched eunuch Grand Admiral, Zhèng Hé (郑和) on seven voyages to the Western (Indian) Ocean. During these most remarkable voyages, in terms of distance travelled, number of crew, size of the fleet and vessel dimensions, Zheng He brought Chinese influence and ideals to the coastal peoples of Asia, India, Africa and Arabia on a scale never seen before. The voyages ended in 1433 when China turned in on itself, banning ocean-going trade and, amongst other initiatives, closing its doors to foreigners. To this day, Zheng He’s voyages are still considered some of the greatest of maritime history, and yet remain virtually unknown in the western world.

Conjecture surrounds many aspects of these voyages, notably the size and construction of Zhèng Hé’s Treasure Ships (Bǎochuán’s 宝船), so named because of the vast quantities of ‘treasure’ that could be carried in their holds. The principal issue is whether, given the technology and resources available at that time, it would have been possible to build and sails ships of the reported dimensions. If these dimensions (approximately 125-metres long by 50-metres wide) are anywhere near correct, Zheng He’s treasure ships were by far the largest wooden vessels ever built. Debate centres on whether ships built before the European age of iron and steel could have the longitudinal strength and structural integrity necessary to successfully carry out the voyages, as recorded in the Ming Veritable Records (Míng shílù 明實錄) and other sources.

The Treasure Ships’ viability has been questioned largely based on Western analogues, notably those of the nineteenth-century British Mersey-class frigates. HMS Orlando and her sister ship Mersey were the longest wooden warships built for Royal Navy. At 336 feet in length, HMS Mersey was near twice the size of HMS Victory, the flagship of Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar. The longest, largest and most powerful single-decked wooden fighting ships that had ever been built, both were considered particularly unsuccessful. HMS Orlando showed signs of structural failure after an 1863 voyage to the United States. Orlando was scrapped in 1871 and the Mersey soon after. They suffered from the strain of their length, proving too weak to face a ship of the line in close quarters. The construction and use histories of these ships indicated that they were already pushing or had exceeded the practical limits for the size of wooden ships.

If wooden vessels are structurally unsound at this size; are the recorded dimensions of Zheng He’s ships incorrect? If they did exist, how and why, did the Chinese build and operate wooden vessels that were more than 40% longer and 65% wider than the largest wooden ships known elsewhere in the world?

My new research seeks to address these questions and more. Traditional Chinese ship design and technology, and the evidence for it, will be re-examined to determine structural features unique to Chinese shipbuilding, and redefine the Chinese tradition. Plans of treasure ship will be reconstructed, modelled and hydrodynamically tested in a towing-tank using ship science approach. The results were published in early 2022, so please watch this space.

1 thought on “Zheng He’s Treasure Ships: myth or reality?”

Very cool always wondered about this.

Comments are closed.