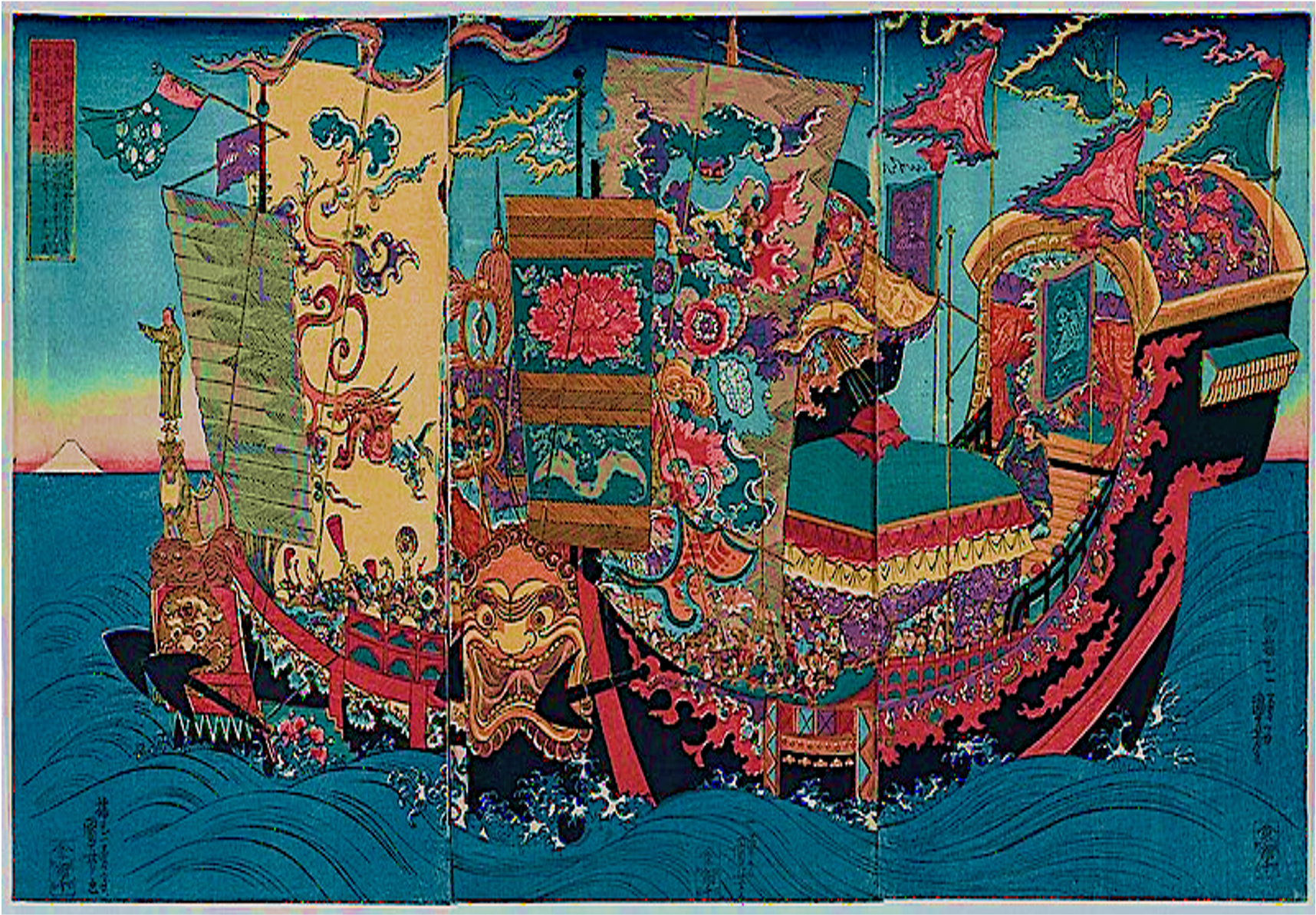

Last week, I wrote of China’s Swimming Dragons, the ships which plied the Maritime Silk Route and to a certain extent still do. I revisited the term Maritime Silk Route, revealed its real meaning, and introduced you to the Nanhai One (Nánhǎi yī hào 南海一号), China’s magnificent Southern Song Dynasty (Nánsòng dài 南宋代) Silk Route shipwreck.

Here, in the second of this two-part series, I explore some of China’s spectacular Silk Route shipwrecks; those that have plied the Maritime Silk Route for millennia and which contributed to the development of the worlds greatest civilisations. Together with Nanhai One, they are the most significant shipwrecks discovered in Chinese waters. They are also sites I’ve seen, researched or personally had some involvement with, and, they have the possibility to tell us a tremendous amount about trade and cultural exchange along the maritime silk route!

So let’s begin…

Quanzhou Ship

Discovered in 1973 whilst dredging a canal at Houzhou (Hòuzhōu 后洲), approximately 10km from Quanzhou (Quánzhōu 泉州), Fujian Province (Fújiàn shěng 福建省) and preserved up to the waterline, the Quanzhou ship (Quánzhōu wān gǔ chuán 泉州湾古船) was one of the earliest maritime archaeological excavations in China. Dated to approximately 1277 CE, the ship remains one of the most important finds to date, as it provides significant physical evidence of shipbuilding and international maritime trade in China’s Song Dynasty (Sòngcháo 宋朝). The remains measure 24-metres long by nine meters wide and consist of the keel, part of the transom, thirteen bulkheads with limber holes (the same number reported by Marco Polo in his Travels), fourteen strakes on the port side and sixteen strakes on the starboard side. Interpreted as being of Fuchuan (Fú chuán 福船) style, the ship was originally thought to be 34-metres long, have a beam of 11-metres, a draft of 3.33-metres, and an estimated cargo capacity of 250 tonnes, and a reconstructed displacement of about 380 tonnes.

A Chinese vessel that appears to have been repaired in Southeast Asia, the cargo composition suggests that the Quanzhou ship was a private merchant vessel returning to Quanzhou. Only a relatively small number (511, including 504 copper and 7 iron coins) of coins were found on board, compared to the 28 tons of copper coins that were found with the Sinan wreck off the Korean coast (more on this another day). This is consistent, it is thought, with the merchants having spent most of their money buying goods to sell in the Song markets.

The primary cargo of the ship was incense wood; around 2,400 kilograms, was recovered from 12 out of the 13 compartments of the ship. There were also small amounts of various other valuable commodities, including almost four kilograms of mercury, and a selection of black pepper, ambergris (which, according to chemical testing, came from Somalia), frankincense (believed to be from the Arab region), a small amount of “dragon’s blood” (a bright red pant resin used as a varnish, medicine, incense and dye), haematite, and one turtle shell. There were also 2,000 cowrie shells aboard. At the time, cowrie shells were widely used as currency in the Indian Ocean and were collected in the Maldives, Sri Lanka, along the Malabar coast of India, in Borneo and various parts of the African coast from Ras Hafun to Mozambique.

Huaguang Reef One

Huaguang Reef One (Magnificent Reef One or Huá guāng jiāo yī hào 华光礁一号) is also the wreck of a Chinese merchant ship built during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279 CE). The ship sank off the coast of the Paracel Islands (Xīshā qúndǎo 西沙群岛) located approximately 330 kilometres southeast of Hainan Province (Hǎinán shěng 海南省 ) in the South China Sea (Nánhǎi 南海).

In 1996, a group of Chinese fishermen discovered remains of the 20-metre long, six-metre wide ship in approximately three meters water depth at Huaguang Reef. The wreckage was spread over 180 square meters suggesting that the ship broke its back on the reef, it was broken up, and its remains scattered by wave action. In March 2007, an archaeological investigation was organised by the National Museum of China and the Hainan Provincial Administration of Culture.

Sadly, the wreck was heavily looted and severely damaged by treasure hunters in the process. Despite this, archaeologists still retrieved more than 10,000 pieces of pottery, porcelain and metalware. Post-excavation analysis proved that most of the porcelain originated from kilns in Fujian and Guangdong provinces. The hull timbers were recovered during excavation. These are currently being conserved in preparation for the wreck’s reconstruction and display.

Huaguang Reef One is significant for its rarity and representativeness. It is also the oldest ship remains that Chinese archaeologists have excavated in the open sea. According to Dr Zhang Wei, then Director of China’s Underwater Research Centre at the National Museum, it provides undeniable evidence of an already well-established Sino-foreign maritime trade routes in existence in the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), as further evidenced also by the Nanhai One and Quanzhou ship.

Nan’ao One

Nan’ao One (Nán’ào yī hào 南澳一号) is an almost intact late Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE) shipwreck ever discovered. Found by fishermen in May 2007, the remains were that of a 25.5-metre long, 7.5-metre wide Chinese merchant ship. It was identified off the coast of Nan’ao Island (Nán’ào dǎo 南澳岛), about 5.6 nautical miles from the 19th Century treaty port city of Shantou (Shàntóu shì 汕头市), in Guangdong Province (Guǎngdōng shěng 广东省). It is also the first shipwreck from the reign of the Wanli Emperor (Wànlì dì 萬曆帝) (1573–1620 CE) to have been identified, and from its hull, over 20,000 artefacts were recovered. These were primarily blue and white porcelains, iron and copper wares, soil samples, metal samples, and animal and plant remains.

One of China’s Great 10 National Archaeological New Finds of 2010, Nan’ao One was singled out as being of particular importance for its potential to provide new information about Sino-foreign trade and cultural exchange in the late Ming dynasty. It was also deemed to be a successful exercise of the development of underwater archaeology in China.

Wan Reef One

Wan (Bowl) Reef One (Wǎn jiāo yī hào 碗礁一号) is an ancient Chinese merchant ship that sank off the coast of Pingtan County (Píng tán xiàn 平潭县), Fujian Province in China’s last dynasty, the Qing (Qīngcháo 清朝)(1644-1911 CE).

Discovered in 2005 and fully excavated in 2008, Wanjiao One was originally 13.8-metre long, with a three-metre wide beam and a one-metre draft. As with the aforementioned ships, it was laden with porcelain. More than 17,000 pieces were recovered, 10,000 of which were rare blue-and-white porcelain from the Kangxi Emperor’s (Kāngxī dì 康熙帝) reign (1654-1722 CE). One small excavated plate is especially noteworthy. The plate was decorated with plum blossoms, and on its underside, ‘双龙’ (Shuānglóng or double dragons) were written in simplified Chinese characters. As you may well know, simplified characters were only introduced at the end of the Republican Era in 1949 CE. So does an almost 400 year-old-plate contain writing adopted barely 70 years ago? It is considered unlikely to be any discernible pattern, and so it remains a mystery.

It is not the only mystery of China’s Silk Route Shipwrecks. In the coming weeks, I will reveal more.